Transcending Victimhood: Robert Gillett and the Importance of Examining Limiting Beliefs

It is important that we examine our own beliefs as individuals. Rather than pointing outside ourselves at what is wrong, we can begin to make peace inside ourselves through the type of non-judgmental observation I described in the chapter on beginner’s mind. We can begin to see how our culture and our own individual beliefs are connected. As Jiddu Krishnamurti remarks, “What we must realize is that we are not only conditioned by environment, but that we are the environment—we are not something apart from it. Our thoughts and responses are conditioned by values which society, of which we are a part, has imposed on us (56-7).

Gloria Karpinski puts it thus in Barefoot on Holy Ground: Twelve Lessons In Spiritual Craftsmanship: “Our whole consciousness, expressed through the body, emotions, and mind, is in constant process with our many environments—the immediate ones, the remembered ones, and the ones we fantasize” (84). The repercussions of this are significant, for what we can be and do is limited (more often than not) by our beliefs and their corresponding actions. Karpinski writes in Where Two Worlds Touch: Spiritual Rites of Passage, “Whatever you believe is true—for you. We do not act outside our perception of reality. Whatever shape and structure our belief system takes on any subject is our “form.” Our forms allow us to express ourselves within the parameters of whatever we perceive ourselves to be. Good, bad, possible, impossible—these concepts are meaningful to us to the degree that we believe them” (73). By examining our beliefs, we can see more clearly the ways in which we are complicit with our culture’s morés and practices. We can get to know the ways in which we have been seduced or coerced into participation and compliance with societal norms. We are then better able to pragmatically choose for ourselves if these endorsed beliefs and practices our actually serving us. Intimately understanding our beliefs takes away their power over us, freeing up space in which we can choose our beliefs with awareness. In this section I try to illuminate how beliefs function so that we might have more insight into them.

Richard Gillett quips that “It is more work to maintain a belief than a car” (53). We don’t notice the work that we are doing, however, because it is mostly automatic and unconscious. Gillett breaks down the things that we do in order to “keep our precious beliefs intact.” He describes how we make life choices that both reflect and confirm our beliefs about ourselves and our beliefs about others. He contends, “To some extent we choose situations and people that fit our perceptions” (53). He gives two examples, “A woman who believes that change is dangerous will choose secure relationships and a secure working situation so that she does not have to test out change. A man who believes he is stupid will choose manual work or repetitive mental work requiring little creativity or initiative—in this way he never develops his mind and is able to retain his belief” (53). These people he describes never test the validity of their beliefs. Instead, they choose actions and situations that are based upon their beliefs and help maintain them.

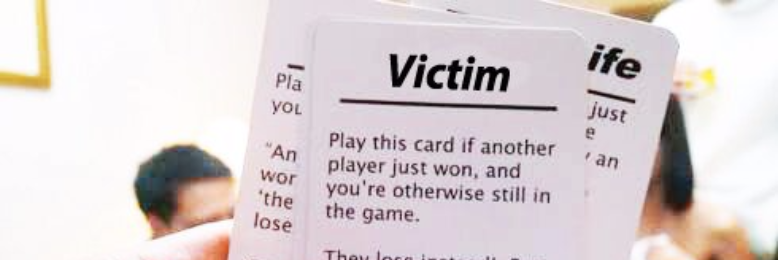

For example, I’m sure we all know (or perhaps are) someone who is always the victim in every story told. Even in stories where the person seems to come out triumphant, s/he insists that s/he was somehow victimized. Energy medicine pioneer and author Caroline Myss has this to say about the origins of victimhood:

Being a Victim is a common fear. The Victim archetype may manifest the first time you don’t get what you want or need; are abused by a parent, playmate, sibling, or teacher; or are accused of or punished for something you didn’t do. You may suppress your outrage at the injustice if the victimizer is bigger and more powerful than you. But at a certain point you discover a perverse advantage to being the victim (116).

This advantage is the reason that the victim often clings to and insists upon that identity. S/he goes to great lengths to maintain the role, filtering out experiences and situations that contradict his/her belief in his/her victimhood. S/he might remember the same situation differently than others who were present. S/he takes the truth and manipulates it to support his/her beliefs. Much of this is done unconsciously, or on a continuum of awareness. Steven Covey writes about this in Principle-Centered Leadership, a follow-up book to his wildly popular Seven Habits of Highly Effective People. He places victimhood at the low end of a spectrum measuring effectiveness, with self-awareness at the high end. He sees victimhood as a lack of self-awareness. He writes:

At the upper end of the continuum toward increasing effectiveness is self-awareness: “I know my tendencies, I know the scripts or programs that are in me, but I am not those scripts. I can rewrite my scripts.” You are aware that you are the creative force in your life. You are not the victim of conditions or conditioning. You can choose your response to any situation, to any person. Between what happens to you and your response is a degree of freedom. And the more you exercise that freedom, the larger it will become. As you work in your circle of influence and exercise that freedom, gradually you will stop being a “hot reactor” (meaning there’s little separation between stimulus and response) and start being a cool, responsible chooser—no matter what your genetic makeup, no matter how you were raised, no matter what your childhood experiences were or what the environment is. In your freedom to choose your response lies the power to achieve growth and happiness (42).

Viewing victimhood in this way acknowledges that while there may be real or imagined limitations existing in the world, we cannot know for sure how much the world is actually oppressing us until we stop oppressing ourselves. For surely we can name at least a few people who have come from circumstances far worse (in our judgment) than our own and have somehow soared far higher than we ever imagined possible for ourselves. We can attribute it to genius or luck, if that serves us. But it is also possible to see these people as able to transcend and transgress the limits enforced by others in order to realize the potential within themselves by simply refusing to believe what the world tells them about themselves.

This type of belief maintenance is done not just with victims but with a variety of identity roles. We look around for evidence that supports our beliefs, and look right past any information that doesn’t, or even contradicts them. We see, by and large, what we want to see. Thus does a belief become a self-fulfilling prophecy. While the phrase “self-fulfilling prophecy” smacks of some sort of hocus-pocus, Gillett explains that it is simply the way in which our pre-existing thought causes us to treat others as if our thought were already true. He contends that it is actually our thoughts and actions that call forth in the other the very behavior or quality we were guarding ourselves against.

The self-fulfilling prophecy of the man who believes “women are manipulative” goes something like this: “Women are manipulative, therefore I won’t trust her.” Because she feels treated with suspicion, she keeps her distance from him. Intimacy therefore disappears and they are left with a relationship of emotional dishonesty and mental manipulation. The part she takes in that process proves that “women are manipulative.” Of course, people are hardly ever aware of the mechanism behind the self fulfilling prophecy. Events happen that seem to vindicate the belief-- the man does really act like a brute and the woman does really manipulate, and both are unaware of the strings they pulled to create or manifest that reality in the other (52).

Although we do not notice our own role in bringing our self-fulfilling prophesies to fruition, Gillett argues that we “mold, select from, exaggerate, or distort the past to make it support our current belief. The process is so automatic, however, that we do not even realize our own bias” (55).

We also rationalize contradictory evidence when it does arise. “Rationalization,” Gillett explains, “Is the last ditch attempt, when all else has failed, to make the aberrant world fit the confines of a belief system” (59). We use the imagined future to support our stance, often giving reasons why “it’ll never work” or “it’ll never happen.” We use our imaginations against ourselves to manufacture an undesirable or impossible outcome. We often assume our reality will remain the same into perpetuity. The imagined result, Gillett maintains, directly impacts what we believe is possible in the present. If I believe “I am never going to get out of debt,” I will not bother to attempt to try by changing my spending habits. If I believe “I am never going to lose weight,” I will feel like it doesn’t really matter if I eat this donut now. This keeps us from changing, keeps us stuck in the same cycles.

Our beliefs also impact the future by filtering the past. Ekhart Tolle, a prominent spiritual teacher explains how the past functions to limit beliefs in the present. He refers to the egoic mind, or the mind wrapped up in “self”-consciousness. He writes:

The egoic mind is completely conditioned by the past. Its conditioning is twofold: It consists of content and structure. In the case of a child who cries in deep suffering because his toy has been taken away, the toy represents content. It is interchangeable with any other content, any other toy or object. The content you identify with is conditioned by your environment, your upbringing, and surrounding culture. Whether the child is rich or poor, whether the toy is a piece of wood shaped like an animal or a sophisticated electronic gadget makes no difference as far as the suffering caused by its loss is concerned. The reason why such acute suffering occurs is concealed in the word ‘my,’ and it is structural (34).

Tolle explains an important force at play in all of these manipulations, “One of the most basic mind structures through which the ego comes into existence is identification. The word ‘identification’ is derived from the Latin word idem, meaning ‘same’ and facere, which means ‘to make.’ So when I identify with something, I ‘make it the same.’ The same as what? The same as I. I endow it with a sense of self, and so it becomes part of my ‘identity’” (35). This identification is ultimately what causes our suffering when we are painfully reminded that we are not the thing we have convinced ourselves that we are. Whatever the identification, whether with a material thing like a car or a house, or with a title or occupation, or with a role such as mother or doctor, or an emotional state like grief or depression, or with one’s race or gender, religion or sexual preference—it is ultimately a construction of our mind, as Tolle asserts, in which we make the thing the same as us. The deep identification with a label or role causes the person to consistently interpret whatever content s/he is given such that it fits into the pre-determined structure that is in keeping with his beliefs about himself. We become in our mind these things that are really little more than practices that we have chosen.

Tolle explains, "What kind of things you identify with will vary from person to person according to age, gender, income, social class, fashion, the surrounding culture, and so on. What you identify with is all to do with content; whereas, the unconscious compulsion to identify is structural” (36). This idea of content as separate and apart from structure is a useful one. It shows the mechanisms at work so that a victim, for example, can maintain the structure of his victimhood while changing the content to suit the occasion. So closely identified is the victim with his victimhood that he often does not see the structure, only the content, which in his mind justifies or vindicates his thoughts or actions. It is by examining the structure—the way in which the victim seeks out situations in which he will be victimized, manipulates the elements in the situation to render himself the victim, or only notices situations that confirm his victimhood—that the victim can stop looking at the content and start looking at himself. Victimhood is a locus of power. There is tremendous power in articulating what is not possible, what I can't do, what is not available to me. Many of the prisons in life are self constructed, based upon our firm reliance on limiting beliefs.

The Advantages of Limiting Beliefs

There are many advantages to maintaining limiting beliefs. One advantage is what Gillett calls “the ego advantage.” This refers to the way that “with great dexterity of mind, any belief, however narrow, can be converted into a personal superiority” (44). Gillett contends that we are able to take our weaknesses and turn them—in our own minds—into strengths. He discusses how we are able to see ourselves as superior to others based on a structure that perceives a quality in them as a flaw or disagreeable or negative, then views the very same quality in ourselves as positive. We do this by sugar-coating the trait linguistically and making it in line with our beliefs about what is worthwhile or positive, recasting what we have shunned in another as a prized trait in ourselves. Gillett provides some wonderfully clear examples:

Take the situation of the man who has difficulty in crying or being tender: It is usually much easier for him to think to himself “I’m a man”; “I’m not weak”; “I’m strong”; “I can take it,” than it is for him to admit his own difficulty with, or even disapproval of, tenderness. It is easier to say: “I know what’s best for me” than to admit you are frightened of change because you have an old belief that change is dangerous. It is easier to consider “I am above money” or “money is dirty” than to face the possibility that you cannot successfully sell goods because you do not really believe you are good enough. Quite often underlying beliefs are lightly hidden beneath a sugar-coating of ego, which makes the belief palatable (44).

Thus, our inability to keep a job is seen in ourselves as “free spiritedness,” our unwillingness to commit to a relationship is attributed to our positive quality of “being picky” or “not settling.” We find ways to spin our misdeeds into virtues in our own minds. We then judge others who do not share our limited belief. As Gillett describes, “The man who has difficulty being tender calls the man who weeps ‘soft.’ The woman who is frightened of change calls the person who changes freely ‘inconsistent’ or ‘untrustworthy.’ The man who cannot sell his product thinks of the successful salesperson as a ‘money-grabber’” (45). As he explains, “The worst liabilities can become marvelous assets” (45).

Another advantage to limiting beliefs that Gillett points out is the illusion of safety that accompanies them. Gillett explains, “As long as we stay within the confines of our belief systems, we are afforded a feeling of security. There is no need for the anxiety of uncertainty because any new input will be rejected before it is effective, or else distorted to fit the parameters of our beliefs” (47). Gillett contends that we reject new information, not allowing it to permeate our consciousness, or we force it into accordance with our pre-set beliefs. Gillett asserts that this is true even when the beliefs create dangerous situations for the believer:

For example, women who believe “men are violent” or “I deserve to be mistreated by a man” tend to choose violent men over and over again. Although they are genuinely fearful and do not like pain or humiliation, the “old situation” provides a paradoxical sense of security. The familiarity of a repeated situation, created by a belief, somehow feels like home. We know the score. We know the rules of the game. Spiritual teachers say that it’s necessary to repeat situations until we master what we need to learn. There is certainly a curious attraction to repeat experiences that fit with a limited belief, and this continues until we learn to change the belief (47).

The predictability of the outcome makes the situations feel comfortable and familiar. We know the outcome before we even get to the end, mainly because we are helping create it. When it arrives, we think “I knew this would happen!” Whether “this” is getting rejected by a friend, cheating on a new girlfriend, being bested by a sibling, or feeling abandoned by a parent, our limiting beliefs help bring it to fruition. Gillett explains the mechanisms of such prediction:

First, our interpretation and perception of events are distorted to fit into our system of belief. If you don’t like somebody, for example, they look uglier and your interpretation of their motives is tainted with suspicion. Secondly, we selectively remember and perceive events that fit our beliefs, and selectively forget and ignore events that do not fit. If you think the world is an awful place, you will notice and focus on the one dead leaf in a bunch of beautiful flowers. Thirdly, we make life choices that fit our belief. For example, if you are a woman who believes “men are brutes,” you will have a tendency to marry brutes. If you are a man who believes women are manipulative, you will tend to choose manipulative women. Fourthly, implicit in every belief is a self-fulfilling prophecy. I have always found that there is a rational explanation how a belief gets translated into reality (51).

Holding limiting beliefs ultimately makes us less responsible for the outcomes in our lives. As Gillett says, “it exonerates us from action” (49). Why bother when we know it won’t work out anyway? I have had many people tell me what they want to do, and when I give them encouragement and support, they start their list of reasons why they can’t do it. Most of these are projections, “my husband would never let me go back to school,” assumptions, “I probably couldn’t qualify for a loan,” or recollections of past events, “the last time I started working out I pulled a muscle,” or even associations with unrelated information, like “my parents are divorced, so I’m not sure I’m cut out for marriage.” We don’t have to try, don’t have to challenge ourselves. We don’t have to do anything really. And we don’t. We dream of greatness while clinging to our safe, limited versions of what we are and what we are capable of. We determine what causes us pleasure and what causes us displeasure, and we try to live such that we only encounter and experience the pleasurable things. While it is arguable that these likes and dislikes are simply judgments that prevent us from being fully present and accepting what is, I hardly expect any of us to rush out and order a plate of our least favorite food. It is perhaps even instinctual that we endeavor to create a safe and comfortable environment for ourselves, as relatively vulnerable creatures that protect ourselves mostly with our minds. But, over time, for many of us, our preference of safety and comfort takes over and becomes rigid. We know what we like and we’re not too interested in experimenting, not even with things we have never experienced.

Gillett argues that even our body language and facial expressions help to attract the situations that fit our beliefs. He contends that “We are all equipped with an automatic, unconscious understanding of the basic body language that constitutes genuineness” (59). We communicate our beliefs about ourselves with our bodies as well as our minds. “A woman with wide-open eyes, slightly caved-in chest, raised shoulders, and shaking hands is proclaiming through her patterns of muscular tension and the stance of her body: ‘I’m scared—protect me.’ This message acts as an aphrodisiac on all those men who believe ‘I am the great protector.’ Like moths drawn to a light, these men will pursue her one after another” (54). Our body is informed by our beliefs and many of our physical illnesses can be traced to problematic limiting beliefs as well.

Above and beyond all the ways that we maintain our beliefs previously described, we do one very important and insidious thing: we manufacture feelings that support our beliefs. While we often rely on our feelings and often take them as “truth,” Gillet argues that “Many feelings are no more than emotional representations of the restrictions of the mind” (61). In the example of racial prejudice, “A person has to have the prejudice—the misinterpretation—before he or she can feel the hate. Feelings are easily manufactured from attitudes” (61). We often use our feelings to validate our beliefs, ignoring the ways in which they inform one another.

While we may (or may) not be able to control the events that occur in our lives, it is inarguable that we can control our responses and reactions to them. What might be the moment to throw in the towel for most is the moment for a few others to try harder with renewed conviction. What might be life ending for some is life-beginning for a few others. It all depends on our own perspective of the events of our lives, our positive or negative judgments of those events, and who we see ourselves to be in relationship to those events. One guy gets into a car accident, loses his legs, and becomes a depressed, reclusive alcoholic; another guy gets into a car accident, loses his legs, and ends up winning the Special Olympics for downhill skiing a few years later. Our choices depend on our perspective.

Becoming Aware of Limiting Beliefs

As Stephen Levine pointed out in Meetings at the Edge “…growth is really a letting go of those places of holding beyond which we seldom venture. That edge is our cage, our imagined limitations, our attachment to old models of who we think we are, or should be. It is our edges that define what we consider ‘safe territory’” (44). Understanding that limiting beliefs exist, and that we create our reality with our thoughts to a larger extent than we often acknowledge, is an important first step toward change. We are able to take responsibility for our lives to a greater degree.

The next step is to diagnose and decipher our own limiting beliefs. Some of these will be obvious, others will be much more subtle and obscured. This is where it stops being an intellectual exercise and becomes a personal and embodied one. Gillett gives some guidelines for diagnosing your beliefs.

Get a notebook and sit in a relaxed position. It is important to answer the following questions quickly and without censorship. Allow yourself to be irrational—allow yourself to write down things that you disapprove of or that you are not sure of. Making a mistake will cause no harm, but trying to avoid mistakes will stop you from discovering anything you don’t know… Go over these…questions a day or two later. Do not make any deletions but add on any other thoughts or feelings that come up. Do not be concerned if there are contradictions. You will find that your answers provide a rich supply of beliefs and self-imposed limits (124-125).

His suggestion of an automatic writing process is intended to keep you, the writer, from self-editing. The editing itself would be a form of judgment and, as such, counterproductive to the exercise. He then offers several questions to answer honestly. Some of these are:

“What are my goals in life?” He notes that “They do not need to be realistic in terms of your present situation and they should not take into account anything that anybody else wants or needs from you.” (125)

“What is it that stops me from having these goals right now?” He suggests that “For each goal write down all the things that seem to you to be in the way—aspects of yourself (your body, your feelings, your inner self, your mind, your characteristics), aspects of others, of society, the past, your age, time, loyalties, the inevitable way life is. Write fast. Don’t think too much. Allow yourself to be unreasonable.” (125)

“What do I disapprove of?” He recommends that you “try to make the suggestion into a definitive statement, even if it sounds dogmatic and off the walls. Remember that this is a process of exploration which eventually aims to go beyond the limiting belief. The first step is to have the personal honesty and courage to see what the limiting belief might be.” (128)

“What do the people of things that I disapprove of have in common?”

And then, the clincher, “So what does that make me?” or “How am I different?” or “How am I similar?” Exploring the relationship between your disapproval of others and what that means in terms of your own ego is very interesting.

He then offers a really interesting list of questions that help to identify a lot of beliefs. When you read your responses, they might sound absurd, contradictory, racist, sexist, conservative, unfair, and completely irrational. And that’s okay. The point is not to judge what we think, but to uncover it. The next several questions were quite revelatory for me.

“What were or are my parents’ belief systems?” You can figure this out by remembering or thinking about what they approve(d) and disapprove(d) of? Sometimes your own beliefs will be opposite of your parents beliefs.

“What generalizations about life did I learn from:

My country?

My culture?

My class?

My education?

My color?

My religion?

My gender?

My body image?

My profession?

Other influential people in my life?” (131-2).

Gillett explains, “Once you have dislodged your belief from what you used to think was reality, you are free to create a better belief. Such a simple statement may seem hard to accept at first. Many people have tried positive thinking techniques, only to find them unreal or too good to be true. A limiting belief is, by nature, cynical. When faced with the unlimited, it projects a screen of disbelief: ‘Come on, you've got to be kidding,’ it says. Somehow the old limiting belief is so firmly ingrained in the mind as reality, that the new positive thinking is simply unbelievable” (137). According to Gillett, this simply indicates that there is more work to be done.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Adler, Mortimer J., and Charles Van Doren. How to Read a Book (A Touchstone Book). New York: Touchstone, 1972.

Aizenman, N.C.. "New High In U.S. Prison Numbers." Washington Post 29 Feb. 2008: A01.

Anand, Margo. The Art of Sexual Ecstacy: The Path of Sacred Sexuality for Western Lovers. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher, 1989.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books, 1999.

Atwan, Robert. The Best American Essays. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company, 2009.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays (University of Texas Press Slavic Series). Austin: University of Texas Press, 1982.

Barry, Peter. Beginning Theory: An Introduction to Literary and Cultural Theory (Beginnings). Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 2009.

Baudrillard, Jean. America. New York: Verso, 1989.

Benítez-Rojo, Antonio. The Repeating Island: The Caribbean and the Postmodern Perspective (Post-Contemporary Interventions). London: Duke University Press, 1996.

Bogin, Ruth, and Bert James Loewenberg. Black Women in Nineteenth-Century American Life: Their Words, Their Thoughts, Their Feelings. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1977.

Bonetti, Kay, Greg Michaelson, Speer Morgan, Jo Sapp, and Sam Stowers. Conversations With American Novelists: The Best Interviews from the Missouri Review and the American Audio Prose Library. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1997.

Bouson, J. Brooks. Jamaica Kincaid: Writing Memory, Writing Back to the Mother. Albany, New York: State University Of New York Press, 2006.

Brander Rasmussen, Birgit, Irene J. Nexica, Eric Klinenberg, Matt Wray, Eds. The Making and Unmaking of Whiteness. London: Duke University Press, 2001.

Chopra, Deepak. The Seven Spiritual Laws of Success: A Practical Guide to the Fulfillment of Your Dreams (Chopra, Deepak). San Rafael, CA: Amber-Allen Publ., New World Library, 1994.

Colás, Santiago. Living Invention, or the Way of Julio Cortázar. N/A: N/A, 0.

Colás, Santiago. A Book of Joys: Towards an Immanent Ethics of Close Reading. N/A: N/A, 0.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment (Revised 10th Anniv 2nd Edition). New York: Routledge, 2000.

Condé, Mary and Thorumm Lonsdale. Caribbean Women Writers: Fiction in English. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999.

Cortázar, Julio. Hopscotch. New York: Pantheon, 1995.

Covey, Stephen R.. Principle Centered Leadership. New York City: Free Press, 1992.

Covey, Stephen R.. The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. New York City: Free Press, 2004.

Crenshaw, Kimberle, Neil Gotanda, and Garry Peller. Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement. New York: New Press, 1995.

Dewey, John. Experience And Education. New York City: Free Press, 1997.

Dewey, John. Human Nature and Conduct: An Introduction to Social Psychology. knoxville: Cosimo Classics, 1921.

Dyer, Wayne W.. The Power of Intention. Carlsbad: Hay House, 2005.

Edwards, Justin D.. Understanding Jamaica Kincaid (Understanding Contemporary American Literature). Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press, 2007.

Endore, S. Guy. Babouk. New York: Vanguard, 1934.

Ferguson, Moira. Colonialism and Gender From Mary Wollstonecraft to Jamaica Kincaid. Columbia: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Ferguson, Moira. Jamaica Kincaid: Where the Land Meets the Body. Charlottesville: University Of Virginia Press, 1994.

Filiss, John. "What is Primitivism." Primitivism. 3 July 2009 http://www.primitivism.com/what-is-primitivism.htm>;.

Fletcher, Joyce K.. "Relational Practice: A Feminist Reconstruction of Work." Journal of Management Inquiry 7.2 (1998): 164.

Foucault, Michel. Ethics (Essential Works of Foucault, 1954-1984 , Vol 1). New York: New Press, 2006.

Foucault, Michel. Technologies of the Self: A Seminar With Michel Foucault. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1988.

France, Lisa Respers. "In the Black Culture, A Richness of Hairstory - CNN.com." CNN.com - Breaking News, U.S., World, Weather, Entertainment & Video News. 6 July 2009. 7 July 2009 http://www.cnn.com/2009/LIVING/06/24/bia.black.hair/>;.

Frankenberg, Ruth. Living Spirit, Living Practice: Poetics, Politics, Epistemology. London: Duke University Press, 2004.

Fraser, Jim. Freedom's Plow: Teaching in the Multicultural Classroom. New York: Routledge, 1993.

Frye, Marilyn. Politics Of Reality - Essays In Feminist Theory. Freedom, California: Crossing Press, 1983.

Gates, Henry Louis. Figures in Black: Words, Signs, and the "Racial" Self. New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1989.

Gates, Henry, and Kwame Anthony Appiah. "Race", Writing and Difference. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 1986.

Gillespie, Marcia Ann. "Mirror, Mirror." Essence 1 Jan. 1993: 184.

Gillett, Richard. Change Your Mind, Change Your World. New York: Fireside, 1992.

Hall, Stuart.Questions of Cultural Identity. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Ltd, 1996.

Hanh, Thich Nhat. Peace Is Every Step: The Path of Mindfulness in Everyday Life. United States and Canada: Bantam, 1992.

Hanh, Thich Nhat. The Miracle of Mindfulness. Boston: Beacon Press, 1999.

Hartman, Abbess Zenkei Blanche. "Lecture on Beginner's Mind." Intrex Internet Services. 3 Mar. 2009 http://www.intrex.net/chzg/hartman4.htm>;.

Henson, Darren. "Beginner's Mind by Darren Henson." ! Mew Hing's 18 Daoist Palms System - Main Index - Five Elder Arts - James Lacy. 10 Feb. 2009 http://www.ironpalm.com/beginner.html>;.

hooks, bell, and Cornel West. Breaking Bread Insurgent Black Intellectual Life. Boston: South End Press, 1991.

hooks, bell. Rock My Soul: Black People and Self-Esteem. New York: Washington Square Press, 2004.

hooks, bell. Teaching Community: A Pedagogy of Hope. New York: Routledge, 2003.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge, 1994.

hooks, bell. Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge, 1994.

hooks, bell. Wounds of Passion: A Writing Life. New York: Henry Holt & Company, 1997.

Horkheimer, Theodor W., and Max. Adorno. Dialectic of Enlightenment.. New York: Verso, 1999.

James, William. Pragmatism (The Works of William James). Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1975.

Jealous, Ben. "The 100-Year-Old NAACP Renews the Fight Against Unequal Justice." Essence July 2009: 102.

Johnson, E. Patrick. Appropriating Blackness: Performance and the Politics of Authenticity. London: Duke University Press, 2003.

Kapleau, Roshi Philip. Zen, Merging of East and West. New York: Anchor Doubleday, 1989.

Karpinski, Gloria. Barefoot on Holy Ground: Twelve Lessons in Spiritual Craftsmanship. New York, NY: Wellspring/Ballantine, 2001.

Karpinski, Gloria. Where Two Worlds Touch: Spiritual Rites of Passage. Chicago: Ballantine Books, 1990.

Kegan Gardiner,Judith. Masculinity Studies and Feminist Theory. Columbia: Columbia University Press, 2002.

Kerber, Linda K. U.S. History As Women's History: New Feminist Essays (Gender and American Culture). Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1995.

Khan, Kim. "How Does Your Debt Compare? - MSN Money." Personal Finance and Investing - MSN Money. 1 July 2009 http://moneycentral.msn.com/content/SavingandDebt/P70581.asp>;.

Kieves, Tama J.. "In Times of Change, Wild Magic is Afoot." Kripalu Fall 2008: 58.

Kincaid, Jamaica. "The Estrangement." Harper's Feb. 2009: 24-26.

Kincaid, Jamaica. A Small Place. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000.

Kincaid, Jamaica. Annie John. New York: Book Depot Remainders, 1997.

Kincaid, Jamaica. At the Bottom of the River. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2000.

Kincaid, Jamaica. Autobiography of My Mother. New York: Plume, 1997.

Kincaid, Jamaica. Lucy: A Novel. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002.

Kincaid, Jamaica. Mr. Potter: A Novel. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003.

Kincaid, Jamaica. My Brother. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1998.

Kincaid, Jamaica. My Garden (Book). New York: Farrar Straus Giroux, 1999.

Kozol, Jonathan. Savage Inequalities. New York, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc., 1991.

Krishnamurti, Jiddu. On Freedom. New York: Harperone, 1991.

Krishnamurti, Jiddu. Education and the Significance of Life. New York: Harperone, 1981.

Krishnamurti, Jiddu. Krishnamurti: Reflections on the Self. London: Open Court, 1998.

Lang-Peralta, Linda. Jamaica Kincaid And Caribbean Double Crossings. Newark: University of Delaware Press, 2006.

Levin, Amy K. Africanism and Authenticity in African-American Women's Novels. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2003.

Levine, Stephen. A Gradual Awakening. New York: Anchor, 1989.

Levine, Stephen. Meetings at the Edge: Dialogues with the Grieving and the Dying, the Healing and the Healed. New York: Anchor, 1989.

Lindberg-Seyersted, Brita. Black and Female. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press, 1994.

Lopes, Iraida H. EntreMundos/AmongWorlds: New Perspectives on Gloria E. Anzaldua.(Book review): An article from: MELUS. Chicago: Thomson Gale, 2006.

Marie, Donna, and Ed Perry. Backtalk: Women Writers Speak Out. New York: Rutgers, 1993.

Merton, Thomas. Contemplation in a World of Action. Garden City: Doubleday And Company, 1971.

Merton, Thomas. Spiritual Direction and Meditation. Collegeville, MN: Liturgical Press, 1960.

Mill, John Stuart. The Autobiography of John Stuart Mill. Durham, NC: Arc Manor, 2008.

Millman, Dan. Everyday Enlightenment: The Twelve Gateways to Personal Growth. New York: Grand Central Publishing, 1999.

"Miracle - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia." Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. 26 May 2009 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Miracle>;.

Moore, John W. "Education: Commodity, Come-On, or Commitment?" Journal of Chemical Education 77.7 (2000): 805.

Moya, Paula M. L. and Michael R. Hames-García, Eds. Reclaiming Identity: Realist Theory and the Predicament of Postmodernism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

Myss, Caroline. Sacred Contracts: Awakening Your Divine Potential. new york: Three Rivers Press, 2003.

Narain, Decaires. Contemporary Caribbean Women's Poetry: Making Style (Postcolonial Literatures). New York: Routledge, 2004.

Norris, Kathleen (ed.). Leaving New York: Writers Look Back. Saint Paul: Hungry Mind, 1995.

Nye, Andrea, ed. Philosophy of Language: The Big Questions (Philosophy, the Big Questions). Chicago, Illinois : Blackwell Publishing Limited, 1998.

Ouellette, Jennifer. "Symmetry - March 2007 - Essay: Beginner's Mind." Symmetry Magazine. 1 Apr. 2007. 17 Dec. 2008 http://www.symmetrymagazine.org/cms/?pid=1000449>;.

Paravisini-Gebert, Lizabeth. Jamaica Kincaid: A Critical Companion. New York: Greenwood Press, 1999.

Perez-De-Albeniz, Alberto, and Jeremy Holmes. "Meditation: concepts, effects and uses in therapy." International Journal of Psychotherapy 5.1 (2000): 49 – 58.

Perry, Donna. Backtalk: Women Writers Speak Out. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1993.

Prince, Nancy. A Narrative Of The Life And Travels Of Mrs. Nancy Prince (1856). New York: Kessinger Publishing, Llc, 2008.

"Qigong - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia." Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. 5 Sep. 2008 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qi_gong>;.

Rich, Adrienne. Blood Bread and Poetry Selected Prose. London: Trafalgar Square, 1987.

Rosello, Mireille. Declining the Stereotype: Ethnicity and Representation in French Cultures (Contemporary French Culture and Society). Great Britain: Dartmouth, 1998.

Rothenberg, Paula S. White Privilege. New York: Worth Publishers, 2007.

Rumi, Jalal Al-Din. Essential Rumi. New York: Harperone, 2004.

Salzberg, Sharon. "Don't I Know you?." Shambhala Sun Nov. 2008: 25.

Salzberg, Sharon. The Kindness Handbook: A Practical Companion. Louisville: Sounds True, Incorporated, 2008.

Schine, Cathleen. "A World as Cruel as Job's." The New York Times 4 Feb. 1996, New York, sec. 7: 5.

Sekida, Katsuki. Zen Training: Methods and Philosophy (Shambhala Classics). Boston & London: Shambhala, 2005.

Sennett, Richard. Respect in a World of Inequality. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2004.

Simmons, Diane. United States Authors Series - Jamaica Kincaid. new york, new york: Twayne Publishers, 1994.

Suzuki, Shunryu. Zen Mind, Beginner's Mind. New York: Random House Inc, 1972.

Tabb, William. "Globalization and Education." Professional Staff Congress. 5 July 2008 http://www.psc-cuny.org/jcglobalization.htm>;.

Tolle, Eckhart. A New Earth: Awakening to Your Life's Purpose. New York: Penguin, 2008.

Walsh, Neale Donald. Conversations with God: An Uncommon Dialogue Book 1. New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1995.

West, Cornell. Democracy Matters: Winning the Fight Against Imperialism. Boston: Penguin (Non-Classics), 2005.

West, Cornell. Race Matters 2nd Edition. New York: Vintage Books @, 2001.

Williams, Jeffrey J.. The Life of the Mind. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002.

Yaccino, Steven. "Caribbean author discusses books, life." The Columbia Chronicle. 12 May 2008. 15 Jan. 2009 www.columbiachronicle.com/paper/campus.php?id=2892>;.

Ziarek, Ewa. An Ethics of Dissensus: Postmodernity, Feminism, and the Politics of Radical Democracy. Stanford : Stanford University Press, 2002.