Lost & Found: A Story About Love

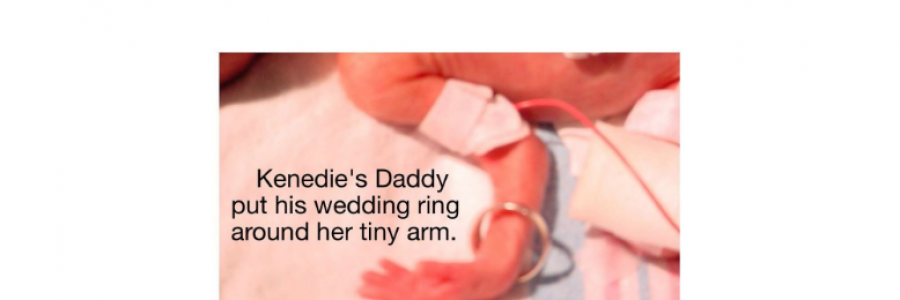

She was born 13 weeks early. Weighed less than two pounds. With pinkish skin. No fat. And a fuzzy head the size of a tennis ball. Wires and tubes spiked her tiny body. (I dubbed her “Spider-Baby.”) Her chances of survival? Flip a coin.

The question for me wasn’t so much, “Would she survive?” but “Could I love her?”

Heartless, right?

Yup. It was. Let me explain …

Love means letting down your guard. Lowering shields. Opening up. That leaves you vulnerable. Unprotected. Exposed to the possibility of pain. Immense pain. (It hurts to lose a loved one. Losing a stranger? Not at all.)

There wasn’t much time to decide. Spidey might not make it through the night. How do you make a decision like that? I didn’t know. Would you?

But first, a little background.

Rachel, my middle child, was pregnant. It would be the first grandbaby for my wife and I. Things seemed to be going well, though the last time I saw Ray-Ray (one of my pet nicknames for her) she didn’t look well. She’d gone to the beach and was radish-red. Her ankles were swollen; her face, puffy. She looked tired and uncomfortable.

A doctor’s visit was in order, but her obstetrician (a woman) was less than sympathetic. In fact, she accused Rachel of using her pregnancy to try and get out of work. (An absurd idea if you knew my daughter, a notoriously hard worker, even as a kid.)

Unsurprisingly, Ray-Ray soon ended up in an emergency room in St. Petersburg, Florida, only to be sent across the Bay (via ambulance) to a woman’s hospital in Tampa. She’d been diagnosed with pre-eclampsia—a potentially dangerous pregnancy complication.

The doctor-on-call that day was an intense, wiry, no-nonsense Italian from New York who knew how to make tough decisions quick. He walked into her room, carrying a chart, and said, “I’m not liking what I’m seeing here. ... We might just have this baby tonight.”

While nurses prepped Rachel for a C-section, my wife and I went to the hospital chapel where I shared with her a Bible verse, 2 Timothy 1:12: “I know whom I have believed, and am persuaded that He is able to keep that which I have committed unto Him against that day.” As we left the chapel, I saw a tract with a lamb on the cover. That reminded me that Rachel’s name meant “little lamb” in Hebrew. I picked up the tract. Inside its glossy pages were the words: “The Lord is my shepherd...” And He was.

The wait-game began.

Intensity and fear worked with anxiety to twist time. Elongate it. Distort it.

Had it been an hour since Ray-Ray went to surgery? Or was it a minute? I couldn’t say.

Finally, we got word: Rachel was OK, but the baby was in the neo-natal intensive care unit. (They’d named her Kenedie, which means “noble warrior.”)

As you’ve probably guessed, I’d decided to love the scrawny Spidey-girl encased in the clear, plastic cube. Never has such a tiny heart captured such a big lug.

Kenedie turns 16 today (April 17). I plan to love her as long as my heart continues to beat. I’m embarrassed and ashamed that I even considered withholding my love. But sometimes welcoming a person into your life, means losing a bit of yourself. It’s a big price to pay—but it’s worth it.

Pretta

Hard Pussy was the one who pointed it out to me. She ran the bar at Butch’s, a narrow joint wedged between the deathtraps and bum flops in Old Town. Butch’s was the first place in the state to buck the local ordinances and offer, as the neon said, LIVE GIRLS TOTALLY NUDE ONSTAGE. Another neon featured a curvy dancer swiveling her hips. You could see it for blocks.

The stage wasn’t much, a single platform thrusting like a dock between the tables. There was no pole or any of that fancy crap that newer clubs had. There wasn’t even a DJ, just an old Seeburg jukebox at the back of the stage, its arc of yellow lights glowing through the haze.

Hard Pussy had been in the Merchant Marine during the war, cutting her hair and passing as a man for the duration. She said her real identity “never came up.” She had a face like a work glove, meaty hands and a genuine Sailor Jerry tattoo on her arm. She’d worked at Butch’s since it opened in 1948, so long that most people thought that she herself was Butch. She’d set them straight on that score if they asked. Most didn’t. There may have been a real Butch, but I never met him.

Butch’s did good business, even in the daytime. There would be at least three or four men in the joint fifteen minutes after it opened at 11, guys with outside sales jobs, cops and firemen, construction workers on lunch. For the talent, Butch’s was either the first rung on the ladder or the last, depending on the dancer’s age and ability. Once in a while there was somebody extraordinary, like the black girl with a bass clef tattooed on her ankle who went on to play with a famous jazz trumpet player in New York City. It was rare, but it happened.

Pretta was a girl like that. I thought so, anyway. She was my favorite. I was in love with her, I realize now. I was twenty-three, new in town. I had no friends, an outside sales job I hated, and the start of a drinking problem. It was a cliché for me to fall for a stripper, but there you have it.

I’d come in and watch her, try to figure out what she was thinking. I knew she was smart because sometimes she’d sit with me and make jokes. I never got to know her at all, but you couldn’t have convinced me of that at the time.

I loved how she leaned against the jukebox, fingers in her mouth while she flipped through the selections. It didn’t matter how carefully she picked. Her music was always shitty. Some dancers have a knack for picking the perfect song, but with Pretta it was just the opposite. The music never fit the mood and was always inappropriate for her style of dancing, if you could even call it a style. Lena Horne and a fast gyration. The Electric Prunes and a slow swivel. It was always just wrong.

I guess she was maybe 20, with a the lovelest face I ever saw in my life. Long black hair like a crow’s wing spilling over high cheekbones and huge dark eyes that seemed half asleep. And a body without flaw, smooth and pearly in the smoke, a figure carved of ivory by a Chinese master. Pretta habitually wore an expression of intriguing blankness, a canvas upon which anything might be written. Sister. Daughter. Whore. Maybe all three.

Hard Pussy gave me my drink, rye and ginger in a beer mug. I offered her a smoke and we lit up. “Say, Charlie,” she said in that diesel voice, low and rattling, “I think you’re shit out of luck. Your honey’s taken up with Doctor Bob.”

Hard Pussy knew I had it bad for Pretta and teased me about it whenever I came in. I tried to always be there when Pretta was working, so lately she’d had plenty of opportunity.

The news about Dr. Bob was bad, but I can’t say it was a surprise. I’d been around long enough to see it happen a few times. Sooner or later Dr. Bob would come in to check out the new girl. He’d stand and watch the stage from across the room, sipping his bottled tonic and not tipping a dime, leaning his pointy elbows on the tall table like he was at a livestock auction. Then he’d leave. This would go on for a while, but one time he’d saunter across the bar and drop a hundred at the dancer’s feet, looking at her face from behind his tinted glasses.

Some girls would fawn all over such big money, but the cooler customers would ignore it like it was fifty cents. It was his test. If the dancer treated the money like shit, then the Doctor would be interested. If she so much as presented her ass to him he’d have nothing more to do with her. More girls than you might think passed the test.

Later, he’d have them over for a table dance or two, talking quietly to them all the while. Hard Pussy frowned on table dances, except for Doctor Bob. He paid for that unique privilege.

Within a few days, the dancer would belong to Dr. Bob. She’d still get up on the stage to do her set, but afterwards she wouldn’t sit at the bar with the other customers. She’d sit with the Doctor and ignore any other overtures.

Hard Pussy didn’t mind because even though Dr. Bob only drank tonic water, he would always drop a hundred or two every time he came in. Hard Pussy didn’t pay the girls. They worked for tips. Some of them cleared five hundred a night.

Usually, Doctor Bob’s chosen would start to put on airs, showing off some new ring, necklace or a dress. Before long she’d be staying up at his house. Sometimes she would disappear for a week or two, showing back up with a cosmetic improvement like new tits or a nose job.

And then she’d be gone altogether. A month or two. Maybe longer. But then she would come back, looking like she’d been though the wars. Hard Pussy told me the longest any girl had stayed gone was six months. That was Jaqui, whose father was a lawyer. Jaqui was hard as rocks about getting her way, an amazon, six-two with red hair and eyes like a pirate. “But even she came back, ” Hard Pussy said. “And she looked worse than all the rest of ’em put together. That Dr. Bob knows how to tear down a woman, chew her up so small she chokes on herself.”

Hard Pussy wouldn’t say what went on up at the Doctor’s house, but I found out later he was a trust-fund MD who didn’t need to practice. He had particular tastes, most of which he’d keep to himself until the moment was right.

With each new girl he would create the illusion that she was the one. And so it would go, Dr. Bob asking more and more until one day she’d refuse him, refuse to allow a further escalation. The next thing the dancer knew she was outside the front gate, lucky if she’d been able to grab an outfit or cabfare. Plenty of girls knew the humiliation of flapping down the streets of the affluent Hills neighborhood in slippers and a teddy, cried-out mascara giving her raccoon eyes as she squinted in the harsh sun. These broken girls would usually dance for maybe a month or two, shadows of their former selves. Then be gone for good.

I figured I knew what Pretta’s fate would be with the Doctor. Everybody did, except Pretta herself. It was like the last act of a farce where all the actors but one are in on the secret and the audience laughs along with them at the fool who hasn’t figured out the obvious. Pretta was mindlessly picking out her music because the poor kid actually thought that her ship had come in. She was positive that within a year she’d be driving around in a Mercedes , a pink poodle on her lap.

My take is this: a guy like Dr. Bob only feels alive when he ruins something beautiful, like a vandal who slashes a Monet. I guess up until he met Pretta, he never found one he couldn’t destroy. Maybe that was why he did what he did.

I was out of town when it happened, but it was spectacular enough that it made it onto the evening news. The neighbors had heard the screaming and called the cops and one of those nightcrawler vultures with a police scanner got there before the police and took that footage that made it to the crime show. Most of it had to be heavily edited because it was too much even for cable, but the blood on the walls and the carpet told enough.

The picture they ran of Pretta must have been from her high school annual. She looked about fifteen, but her eyes still had that look, that never-touch-me stare like she stood alone on some island you could never get to. That look could make a man fall in love, or worse. They gave her real name, too. A little girl’s name. It didn’t fit her. I could see why she had changed it.

I never said goodbye to Hard Pussy. I got a regular job in another town, quit drinking, and settled down with a girl I met at church.

With her long black hair and big dark eyes, my wife looks like she might be Pretta’s sister. But her eyes are different. They invite you in and ask you questions.

It’s not the same kind of love I had for Pretta. It may not be love at all.

But it’ll do.

Ah—choo!

The petals gently swayed in the air, before landing by a statue. If one looked carefully at the figure, and didn’t blink, you’d notice that its nose would twitch. He had always been allergic to jacaranda petals, even now as a stone figure he was quite surprised that they still affected his sinuses.

#Ah—choo!

The Edge of Silence

On the Feast of the First Morning of the First Day, in the Year of the Monkey, 1968, North Vietnam’s wildcat soldiers—many dressed in pale shirts with pleated pockets, button-downed trousers, and wearing sun-helmets or jungle hats—attacked South Vietnam.

Bullets and tracers cracked the silent sky; grenades and mortar fire shook the earth.

Thousands of Americans in hundreds of cities, towns, and villages, faced ever-growing waves of gritty soldiers trying to provoke citizens in the south into overthrowing their own government and siding with Ho Chi Minh and his Communist regime.

It did not happen.

What did happen, however, was a bloody mess: More than 40,000 Viet Cong died, along with 7,000-plus Americans.

I was not in-country during that brutal battle, known as the Tet Offensive. I showed up later.

In 1971, I was given guard duty at the end of a runway at Da Nang Airbase—a runway that had been overrun during Tet.

Spooky.

The night-watch lasted four hours. It was deadly dark. Menacing. On the edge of the jungle—a stone’s throw from hell.

I was alone.

It crossed my mind that somebody was out there. Watching me. From the other side. (Of course they were. Why wouldn’t they be? They were doing their job—like I was doing mine.)

Nighttime creeps me out. Haunts me. Especially that night. Gloomy thoughts conjured up layers of fear, anxiety, and dread. I didn’t need that. Not one bit.

I was wearing a helmet and flack jacket along with my uniform-of-the-day. My weapon: an M1911, Automatic Colt Pistol. The barrel was rusty; sand had found its way into the detachable magazine.

Nobody ever taught me how to shoot a 45—let alone dismantle and clean it. Didn’t really matter. I was told not to load my pistol unless ordered to do so. And, if so ordered, not to shoot unless given an official OK. Good thing, too, because (given the rust and sand) the dang gun would have exploded in my face.

About two hours into the watch, I got paranoid—trees became stalking solders; shifting ground-grass transformed into a dangerous threat. My breathing sounded like labored gasps from a faulty fireplace-bellows; my heartbeats reverberated like hollow thumps rumbling through a defective drum.

At some point I put my hands in my pocket and was surprised to find the harmonica I’d used the night before to play for drinks at the on-base saloon. Of course I wouldn’t play the harmonica out here. Not on watch. For one thing, the sound would call attention to me; for another, the shiny metallic top and bottom plates would make a great target for sharp-shooters.

Playing would be a suicide move.

Eventually, boredom, fear, and dread teamed up to form a strange euphoric alliance. Pragmatic. Morbid. Sinisterly re-assuring. I took out my harmonica and played a sultry blues riff. Panic melted away. Terror took a trip. Apprehension dissipated into wistful puffs, like ghostly smoke leaving a dying fire.

Better target for a sniper? Sure. But I figured I’d rather take a kill-shot than suffer a shattered arm or leg.

Silence sauntered away that night. Quiet as a bug. Far away from my one-man parade—drifting through a stream of blue notes and caressed by a soft, summer breeze.

My So-So Version of “Here Comes Santa Claus”

Here comes mother-in-law,

here comes mother-in-law,

storming down my main street.

She’s got a look on her face,

that says someone’s gonna get beat,

so, I better lock my doors

turn out the lights,

and pretend that I’m not home,

and say my prayers

that mother-in-law doesn’t stop here tonight.

I hear mother-in-law,

I hear mother-in-law,

breathing on my front door,

her hands are filled with a hammer and nails,

and my life’s about to not be the same.

What did I ever do to deserve her into my life?

Guess that’s what happens when the woman I love

has a mother who taught Grinch all the tricks.

Oh what a horrible sight she is,

hurry up, get home honey, I’m about to be fried!

__________

The original by Gene Autry

https://youtu.be/XK60Cwwp_EI

Pyro

You're the fire in my soul,

Can’t keep it down, gonna burn me whole.

They said take I’d better take it slow

But while I’ve got the courage I gotta go.

Maybe we were never meant to be,

But now we just have to see...

Strike a match, and watch it burn

Up my bridges so I can’t return.

Take the ashes, put them in an urn,

Testament for later to the lesson I've learned:

Sometimes you gotta take chances,

And love's one of those complex dances,

You get burned if you mess with a flame

But that's part of the price for playing the game.

The Devil’s Dog

Tick-tock tick-tock, Clark watched the massive black hands in their chopped arithmetical dance. His eyes witnessed the seconds pass. The midnight hour was nigh and the moon full. Thin clouds whisked overhead on the dark canvas night sky. An icy wind pricked his ears and nose like needles. Clark exhaled seeing his breath condense to a foggy ghostly air. He flicked back a wing of his winter night cape and checked to see if Reginald loaded the silver bullets this time. DING-DONG-DING, rang out then a howl only the devil's dog could make. It comes! The beast, it comes now!